In part one of the How Do We Share Power? series, I spoke about the cognitive dissonance between what tech promised the world versus what it actually built, and why we tried a new form of governance—sociocracy—for ourselves. If you haven’t already read part one, I encourage you to do so here.

Part two is about how we implemented sociocracy at Studio Terranova and my own thoughts and learnings from that process.

Back to our retreat in Yamanashi.

It’s an unseasonably brisk day for early June. I have picked our facilitator, Heather up from the local train station. After some thoughtful pre-reading of Many Voices, One Song, we dove into the first part of the day: reviewing the mindset of sociocracy and defining our vision, mission, and aims.

The Mindset of Sociocracy

Power is itself neither good nor bad. What matters is how it’s wielded. Sociocracy sees power like water. When it’s channeled to flow equitably, it can give a voice to all members of an organization. When hoarded, it becomes stagnant. The goal in sociocracy is to share power so that it flows effectively and equitably.

Distilled, sociocracy values equivalence, working within the group’s “range of tolerance” over “range of preference” and encouraging objections.

Equivalence. Involve people in making and evolving decisions that affect them, so that you increase engagement and accountability. Sociocracy lays out a visual framework called circles for different areas of responsibility. Decisions involving this area of responsibility are delegated to a small team. For instance, an HR circle

This is similar to a small team being empowered with design decisions that can take into account feedback from stakeholders and users. However, one key difference is that if a stakeholder wishes to influence the decision-making for the area of responsibility, they must commit to being a part of the circle and the responsibility it entails.

1. Encourages objections. Objections are critical to the group’s formed understanding of where their tolerance is, and so are treated as valuable information, not something to be quashed or ignored. In fact, the process of consent is always opt-in. Silence is not assumed as consent, and if there is silence, it is considered an objection.

2. Working within the group’s “range of tolerance”. It aims to find the option that is not necessarily preferred, but within everyone’s range of safe enough to try.

Something outside of your range of preference but still within your range of tolerance could be:

-

Something you’re not good at, but don’t see the harm in failing

-

Something you are okay doing for a short period of time

-

Something that, if the role were adjusted and it still achieved its aim, you would be okay taking

Next, I’ll go into what the organization of our company looks like now.

Vision Guides the Spirit, Aims guide the work

In sociocracy, it is structured as a broad, “We are dreaming of a world where it is true that…”

I found that sociocracy’s method of generating a “to-be” state proved to be much more open-ended than product design. I liked this because “we make a new product or service and people buy it” isn’t always the solution to the world’s problems. Sometimes they aren’t limited to physical or digital products and services.

There are a lot of dreams we had for the future. We went with: “We are dreaming of a world where it is true that serving community is valued more than serving capital,” as our vision, and “Our mission at Studio Terranova is to explore new frontiers in technology and games.” We value capital the same way we value a place to live and financial independence. However, financial independence at the cost of friends, family, and personal health could hardly be considered a life worth living.

It’s exciting to think big like this. But once we had our vision, only a fraction of our work was done. Now was the time to get our hands dirty in how we would go about building that future—the more specific, the better. These would become our aims.

According to Many Voices, One Song aims should be as specific as possible. A majority of conflicts arise in organizations when everyone agrees on a vision, but does not agree on how the organization achieves that vision.

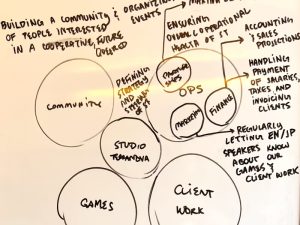

This opened us up to consider things that were not typically “valued” in common for-profit businesses as something that could be part of ours. Our work is, in part, community-funded, but our community’s value is not in how much money they pay us. It is a way for us to give back and find like-minded people. We found ourselves asking these questions:

– But exactly who is our community? In what way do we value them? From this, we created the Community Circle’s aim:

Building a community of people interested in a cooperative, queered future

We specifically chose the word “queered” as a verb—as in “queering games”—something I first heard in reference to game developer Robert Yang’s work. It is not only in reference to the player character being queer, but having queer experiences be seen as “normal” from the viewpoint of everyone in the world.

For our Games Circle, what kinds of games do we make?

Creating queer narrative games for the joyfully alt

mabbees said that he wanted to build a future together with “joyfully alt” people like us, and I agreed. We’re not “alternative” because it’s cool – we’re alternative because it is the way we are; and being able to live more authentically makes us happy. I believe our fans would agree with us.

What about our client work?

Providing high-quality bilingual services (user research, interaction design, UI programming) in Japan on a hybrid basis/full remote basis to organizations that care about how people will use their digital tools

This helps us laser focus on prioritizing and attracting clients that are a good fit to our skills and services.

Finally, in order for our business to function, it must be financially healthy, pay its taxes in Japan, and adhere to our vision. Thus, the aims of both the Operations Circle and General Circle:

In this way, our organizational structure at its core supports our vision of valuing community over capital.

Domains—Giving Us the Authority and Autonomy to Work

Domains are the areas in which circles have authority and agency to do work.

A common misconception of autonomy is that it relies solely on the will of the individual to be autonomous, without taking into account whether or not they have been allowed the authority and agency to act. This can result in a frustrating game where the company expects more of the worker but cannot achieve the results they want because they have a stranglehold on authority. Leadership is burned out on “rescuing” everyone, and everyone else is burned out on consistently having a lack of authority to make a change.

Breaking out of this is not easy. But I’d rather build a community with members I can trust and rely on than one where I am the sole authority who wastes away from burnout.

Let’s dive into our Community Circle, whose aim is to build a community of people interested in a cooperative, queered future.

To achieve that aim, we must maintain spaces, whether it be online or in-person, for people. We have a Discord community for fans of our games, and a Discord that I run as a volunteer for game jams in Tokyo. I also regularly keep in touch with our clients.

So where the Community Circle can act is in our…

-

Games Discord

-

Game Jam Tokyo Discord

-

Volunteer Management

-

Bug Reports and Player Feedback for Games (Steam, itch.io and Discord). They then send them to Games Circle

-

Client Coffees

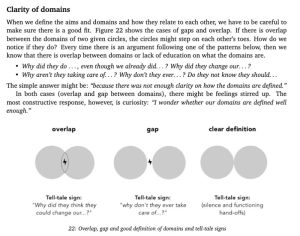

These are the things the Community Circle has full authority to act on. But what happens if there is an overlap or gap with other circles?

Many Voices, One Song, p. 26

For example, the Community Circle handles the communication with players if they experience a bug in our games, but they have a point where they must handoff things to the Games Circle, who have the programming and design expertise to fix those bugs.

There is a possibility that this handover will be a source of conflict. What if the bug is critical but we lack the resources? What if the Games Circle fixes some bugs and doesn’t report to the Community Circle, and players get upset at the Community Circle? These are objections the Community Circle can bring up so that their domain can be properly shaped and adjusted, like so:

-

if the bug takes longer than a week to fix, the Games Circle will tell the Community Circle so they can relay that to the player

-

asking the Games Circle to assess the difficulty of the bug so they can decide whether it is worth the effort to fix

I enjoy this kind of “organizational shaping”—that is, building in enough structure for people to move autonomously but not so much structure that they are too restricted—because it allows us to shape to the level of flexibility or rigidity our company can safely try.

Just like living organisms, organizations can come in all shapes and sizes and levels of tolerance.

Once we had our domains defined to the point where we felt comfortable trying them, we moved on to roles.

Roles

Defining roles proved to be one of the most surprising and eye-opening experiences for me that week. Going through defining roles helped us figure out how much we were doing so that we could delegate or drop things. The blessing and the curse of being only two people is that our time and energy is very limited and since early 2024, a majority of our time in running the studio has been mired in administrative work.

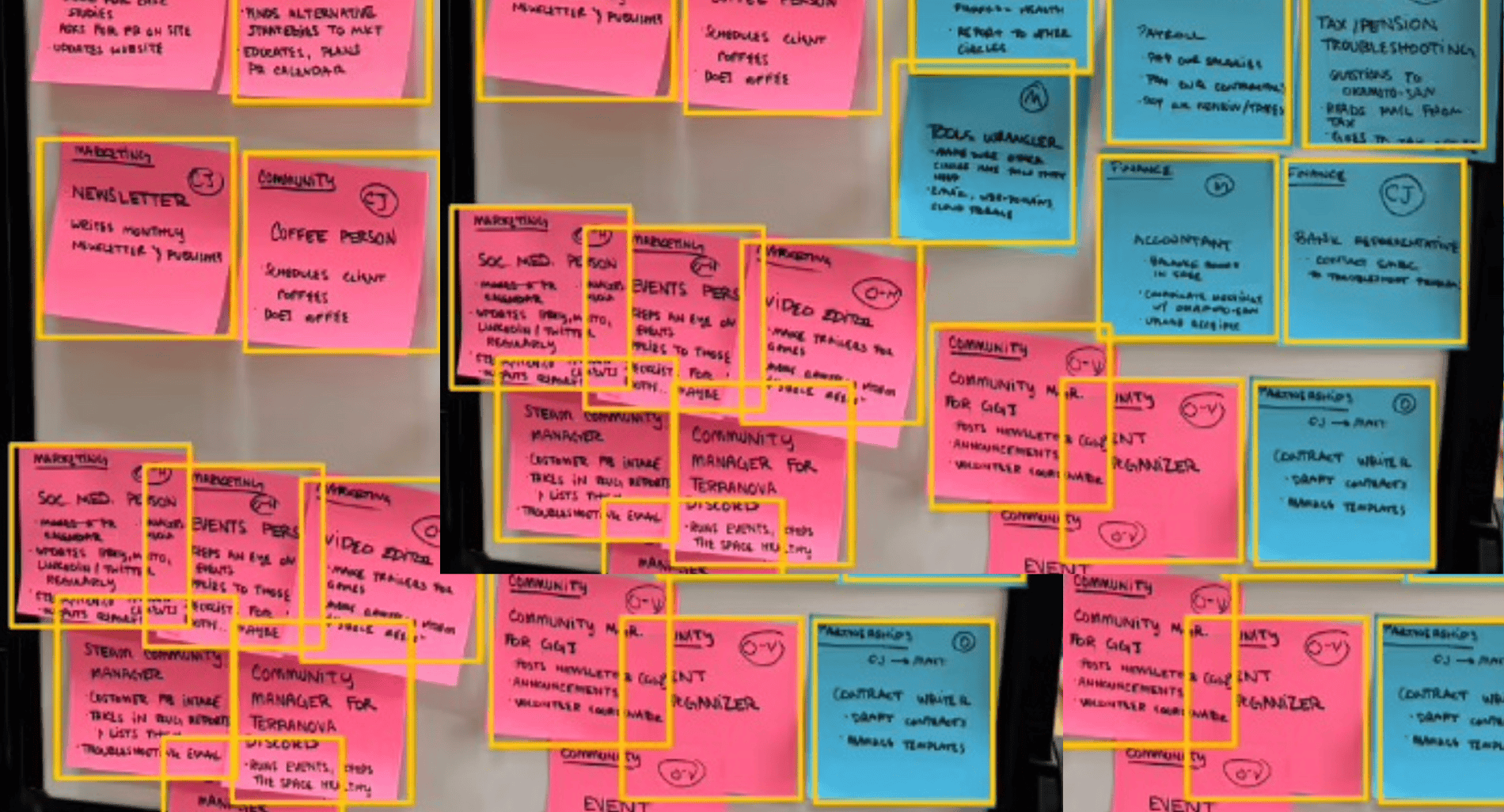

Unlike an LLC in the US, LLCs or 合同会社 in Japan require tax reporting and payments several times a year, accounting, and employment of a tax adviser. This was in addition to client work, video game work, and marketing. By our retreat, we were burned out. The first step to understanding how overworked we were was to lay out our roles. Once we assigned ourselves to lead a circle, we wrote down the roles we’d already been doing, one per sticky note.

The results were humbling.

Out of the 34 roles on this board, I had been handling 24 of them solo.

No wonder I had no time to brainstorm new ideas or make games.

Some strong feelings came up for me, mainly confusion (how did it get so bad?), resentment (why am I doing this alone when I have a co-founder?) and amazement (I didn’t know I could handle that much stress). I had brought up vague feelings of being overworked in the past, but didn’t have the downtime to clarify what roles were being done and what knowledge was needed to do them.

There were a few reasons for this imbalance:

-

I am more confident in communicating in business-level Japanese and many of the administrative tasks required me to call someone or navigate websites in Japanese

-

no skill sharing on my end on around how to do a role, so it appeared I “had it under control” when I was overwhelmed

-

no clear domain or process of consent around picking up roles, so if a deadline was approaching, I’d start to get nervous and proactively pick up a role.

After I processed my mixed feelings, we went through each post-it decided our roles and their term length. Some of the roles we picked up joyfully; others required exploring our personal range of tolerance.

This range can allow us to enter into a healthy dialogue about what parts of the role we object to and how we can shape it. This kind of dialogue was, outside of my romantic partners, the first time I’d had critical, compassionate conversations about where my range of tolerance was listened to and taken into account in a way that both served my needs and others around me.

In Conclusion

We tried out sociocracy at our studio with the hope that we would get connection and clarity in our work—and that, I can happily say, has worked well. In fact, we got more clarity than I expected.

It is more clear who works on what part of our workflow, how we can effectively hand over work and who we need to hire to grow. We made these decisions collaboratively with agreement on both sides. I feel confident that the way we are organized as a cooperative is in alignment with our values; we center both us as people and the work we do.

I mention the book Many Voices one Song throughout. I highly recommend it. We took 10 minutes to read small excerpts from the book before we would make decisions so that everyone was on the same page.

Many thanks to AQ who hosted us, and Heather Dobbin who helped facilitate this retreat.

- Sociocracy for All: Comprehensive guides on what sociocracy is and how to implement it.

- Collective Power: Patterns for a Self-Organized Future: A deeper dive into the mindset of sociocracy.

- Many Voices, One Song: A detailed handbook for implementing sociocracy. I recommend reading “Collective Power” first to thoroughly understand the mindset.

- Rebuiding Community on the (Fujo)Web, pt. 1: About burnout in fandom spaces. From Ms. Boba’s Citrus Con 2024 talk.

- Rebuiding Community on the (Fujo)Web, pt. 2: About how power dynamics need to be challenged to grow. From Ms. Boba’s Citrus Con 2024 talk.