The Invention of Separation

Over time, I have been reflecting on the relationship between humans and what we conventionally refer to as “nature.” But the deeper I delve, the more I realise that the real subject of study may not be that relationship itself, but rather the historical and cultural construction of its absence – the idea of separation between the human and the more-than-human.

This disconnection did not arise by chance.

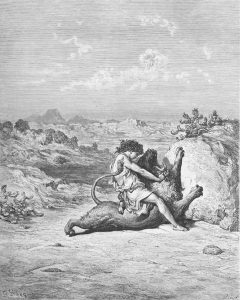

We can trace it back to the founding myths of the West, such as the story of the expulsion from paradise, that symbolic moment when humanity supposedly broke away from communion with the beings and forces of the world. From that point on, fear took hold: fear of the dark, the forest, animals, plants, of what is untamed. As many studies show, this fear feeds the desire for control, domination, and separation. It sustains the fantasy of total domestication, the attempt to reduce the world to what can be named, ordered, and exploited.

Humanity at the Center

Modern thought, through science and philosophy, deepened this abyss. Darwin, when proposing the theory of evolution, broke with religious dogmas but also organised us into separate species. Haeckel placed us at the top of the “tree of life.” A hierarchy was established. Humanity then proclaimed itself the centre and measure of all things.

The colonising and anthropocentric culture that followed turned that distance into the norm. The coloniser not only feels superior but is also entitled to transform, exploit, and domesticate everything encountered. The world became a resource. The other (human or nonhuman) became an object. And so we continued killing for pleasure rather than need; training animals, dominating territories, erasing forests.

When Disconnection Becomes Reality

The result is before us. Recent studies reveal that many children can no longer recognise common trees or animals. The term nature disconnection (Beery et al., 2023) describes not only a loss of contact with the natural world but also a loss of recognition of oneself as part of it. This creates an urgent need to reimagine what we call “nature.”

Rethinking “Nature”

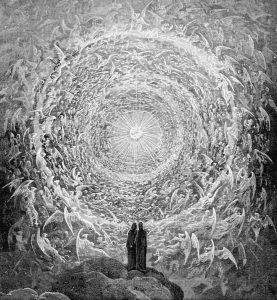

As Timothy Morton reminds us, “nature” is a concept that slips away from us. It is projected as something distant, pure, untouched. But perhaps we need to redo that image. Life is woven through relationships. We are part of a living mesh, interdependent and co-constitutive. As James Gibson proposed, perception is not a passive mirror of the world, but an active mode of being in relation to it.

This shift is also a call to action, a call to a nature-centred design practice. When we design, who do we consider part of the project? Who decides what is natural and what is artificial, who deserves care and who can be discarded? How do our design decisions affect the plurality of voices — human and more-than-human?

From Designing for Humans to Designing with Life

Nature-Centred Design arises as an attempt to respond. It is not about designing inspired by nature, but about radically rethinking the place of design and designers within the web of life. Rather than creating solutions solely for human needs, it invites us to listen, learn, and collaborate with the rhythms, forms, and intelligences of the natural world. Guided by ecological principles, this approach recognises that every creation is embedded within interdependent networks — and that the environment is not a passive backdrop, but an active agent in the co-construction of life.

Thus, rather than defining subjects and objects in static terms, Nature-Centred Design (NCD) proposes designing from relationships: considering impacts, listening to those affected, and cultivating reciprocity. Inspired by perspectives such as Acosta’s buen vivir and the writings of Anna Tsing and Donna Haraway, it asks: “What happens when species meet?” — and more specifically, what happens when species meet within design? NCD invites us to design for cohabitation, for living together.

What kinds of design practices align with this purpose? They include community-led design rooted in place, as well as co-sensing methodologies that value both embodied and traditional ecological knowledge. Bruno Latour’s Politics of Nature, Arturo Escobar’s relationality, and Marisol de la Cadena’s cosmopolitics reinforce the idea that the worlds of mountains, rivers, animals, and spirits must be acknowledged in design decisions. This does not mean anthropomorphising nature, but rather recognising the multiplicity of agencies and realities that coexist on the planet. From this perspective, design becomes a cosmopolitical act — one that configures spaces of encounter, listening, and mutual transformation.

Can We Truly Transform?

Can humans — especially designers — transform themselves deeply enough to transform their impact on the planet? How can we inhabit a world in which industrial progress has revealed its failures? What new narratives and ways of understanding the world can guide us in an age marked by loss? What design practices must be rethought to protect life on Earth better?

Evolving our Design Framework

These questions led to a speculative exploration that sought to add new layers to the Double Diamond Framework and reinterpret Dunne and Raby’s A/B Manifesto, integrating themes such as ecological entanglement, reciprocity, and care into design practice. Reimagining these frameworks from a more-than-human perspective entails challenging human-centred assumptions and expanding their scope to encompass the voices, needs, and agency of nonhuman beings and ecosystems.

The adaptation of the Double Diamond Framework involved recognising ecological entanglements at every stage: discovering not only the needs of human users but also the impacts and contributions of more-than-human actors; defining problems relationally and systemically; developing solutions in partnership with living systems; and delivering outcomes that nurture reciprocity and care among species.

Discover + Attune: Slow down. Listen. Sense the landscape (literal or metaphorical). Who/what is present? What are their rhythms, needs, and relations? Engage with more-than-human entities (e.g., rivers, fungi, insects) through observation, storytelling, and embodied presence.

Define + Co-sense: More than “defining a problem,” hold space for plural perspectives to emerge. Co-sense patterns and tensions with human and more-than-human communities. What matters to the ecosystem? What is asking to emerge? Let the “problem” be relationally shaped, not imposed.

Develop + Grow: Nurture possibilities like a gardener, not a planner. Prototype through collaboration, material responsiveness, and seasonal awareness. Embrace uncertainty. Let materials and organisms participate in shaping the form. Iteration becomes evolution.

Deliver + Reintegrate: More than “delivering,” consider how outcomes return to the web of life. Does it regenerate? Decompose? Feed? Heal? Reintegration honours the cycle. The “end” is not a launch, but a re-entry into ecological and social systems with gratitude and care.

More-than-human Double Diamond (adapted from Design Council’s Double Diamond Framework for Innovation)

Similarly, the A/B Manifesto expands into an A/B/C Manifesto, where design not only presents ecological realities but imagines futures of coexistence and regeneration — fostering multispecies flourishing and ethical interdependence.

| A | B | C |

| Affirmative | Critical | Relational |

| Problem solving | Problem finding | System-healing and relationship-building |

| Provides answers | Asks questions | Cultivates conditions for emergence |

| Design for production | Design for debate | Design for nurture |

| Design as a solution | Design as medium | Design as ecology |

| In the service of industry | In the service of society | In the service of the planet |

| Fictional functions | Functional fictions | Ecological agencies |

| For how the world is | For how the world could be | For the more-than-human world |

| Change the world to suit us | Change us to suit the world | Acknowledging multiple ways of knowing and being |

| Science fiction | Social fiction | Ecological fiction |

| Futures | Parallel worlds | Cosmovision |

| The “real” real | The “unreal” real | Situatedness real |

| Narratives of production | Narratives of consumption | Narratives of plurality and kinship |

| Applications | Implications | Living interactions |

| Fun | Humour | Care |

| Innovation | Provocation | Sensing |

| Concept design | Conceptual design | Regenerative design |

| Consumer | Citizen | Multispecies |

| Makes us buy | Makes us think | Makes us feel responsible with |

| Ergonomics | Rhetoric | Symbiosis |

| User-friendliness | Ethics | Interdependence |

| Process | Authorship | Co-becoming |

A/B/C Manifesto (adapted from Dunne & Raby: A/B Manifesto)

Projects such as Multispecies Design Cards also invite us to consider animals (and plants, rivers, even the planet itself) as users, participants, and co-authors of the spaces we inhabit. Ecological visualisation workshops, like those described by Löfström et al. (2025), reveal the power of disruptive imagery as a trigger for reconnection and collective reflection.

Towards a Shared Future

This transformation requires silence, listening, and unlearning. As Thich Nhat Hanh reminds us, the Earth is calling, but we must be still to hear it. We must recognise that we do not live on the Earth – we are the Earth. We are Nature. And care is not an act of charity, but of recognition.

Reconsidering the human–more-than-human relationship is therefore not only a matter of ecological survival, but of meaning, belonging, and the possibility of a shared future. Walking toward a truly ecological design also means rethinking our metrics: beyond economic growth and technical efficiency, we must value durability, biodiversity, regeneration, and collective well-being. As we draw closer to the Earth, we also reconnect with our own living conditions. And in that gesture may lie the hope of a new beginning.

***

If you found these reflections meaningful, you might enjoy discovering more in Carla Paoliello’s book, ´Nature-Centred Design – when we learn the dialogue of flowers.´ Download its PDF in English, Portuguese, Spanish, or Italian for free at: https://shre.ink/DCN

Connect with Carla Paoliello on LinkedIn to follow her musings and insights.

***

References used in this article:

Acosta, A. (2016). O Bem Viver: uma oportunidade para imaginar outros mundos. Elefante Editora.

Beery, T., et al. (2023). Disconnection from nature: Expanding our understanding of human-nature relations. People and Nature. 5. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10451

De La Cadena, M. (2015). Earth Beings:Ecologies of Practice across Andean Worlds. Duke University Press.

Dunne, A., & Raby, F. (2013). Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. The MIT Press.

Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the pluriverse: Radical interdependence, autonomy, and the making of worlds. Duke University Press.

Gibson, J. (2014) [1979]). The ecological approach to visual perception. Psychology Press.

Haraway, D. (2007). When species meet. University of Minnesota Press.

Latour, B. (2004). Politics of nature: How to bring the sciences into democracy. Harvard University Press.

Löfström, E., et al. (2025). Ecological visualization workshops: Disruption as reconnection. Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1690875/abstract

Metcalfe, D. (n.d.). Multispecies Design Cards. Available at https://danimetcalfe.com/index.php/md/

Morton, T. (2009). Ecology without nature: Rethinking environmental aesthetics. Harvard University Press.

Hanh, T. (2008). The world we have: A Buddhist approach to peace and ecology. Parallax Press.

Tsing, A. (2021). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press.