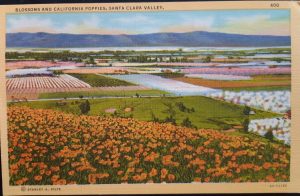

If you had visited California’s Santa Clara Valley in 1940, the biggest revelation happening was how delicious a prune could be. Locals proudly called it The Valley of Heart’s Delight, which sounds like a seedy motel, but was actually referring to peach and apricot orchards stretching across the valley.

Fast-forward 80 years: the same land fuels billion-dollar valuations, global influence, and apps that tell us when to breathe so we don’t forget. Silicon Valley didn’t just invent computers — it rewired how humanity communicates, works, shops, dates, dreams… and yes… panics about AI replacing us.

But behind the hype lies a lesser-told origin story: one rooted in federal funding, elite academia, and rebellious engineers making dramatic exits. This is the real tale of Silicon Valley. And, like any great tech launch, it started with a beta.

When Stanford Got Tired of Losing Talent

Imagine being Stanford University in the 1930s. Smart students were graduating and immediately booking one-way tickets to jobs on the East Coast.

Enter Frederick Terman, Stanford Engineering Dean. He persuaded his brightest protégés, Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard, to stay nearby, start a company, and pursue innovation, where the wine is decent and the winters are mild.

This idea — “don’t leave, innovate here!” — created a loop:

→ Stanford educates engineers

→ Engineers build companies

→ Companies make billions

→ Stanford gets donations

→ Stanford builds nicer labs

→ Repeat until Palo Alto rent hits the stratosphere

And then came the Stanford Research Institute (1951), founding Silicon Valley’s core identity of academia + industry + government = unstoppable tech.

Microchips and Mutiny

Silicon Valley’s first true drama was a workplace rebellion. In 1956, Nobel Prize-winner William Shockley opened a transistor lab in Mountain View. Then led it with the managerial style of “tyrant who tracks your bathroom breaks.” Eight key engineers fled, earning themselves the name “The Traitorous Eight.” Their new company? Fairchild Semiconductor. Their impact? The microelectronics revolution.

“Fairchild created Silicon Valley’s culture of spin-outs, stock options, and risk-taking.”

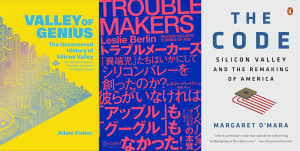

— Leslie Berlin, Stanford Historian and author of “Troublemakers: Silicon Valley’s Coming of Age”.

Fairchild begat National Semiconductor, Intel, AMD, and a cascade of startups. Basically, one big massive split with a multitude of offspring bouncing around.

A Timeline of Growth, Boom, and Tech Identity

| Year | What Broke the World (In a Good Way) |

| 1951 | Stanford Research Institute opens |

| 1957 | Fairchild Semiconductor founded by the “traitorous eight” |

| 1969–1976 | FIVE new industries emerge: semiconductors, video games, PCs, biotech, venture capital |

| 1976 | Apple was founded, sparking the personal-computer era |

| 1995–2000 | The internet boom — and the dot-com crash |

| 2007–2010s | Platform era begins: software, network effects, Big Tech dominance. Google search, Facebook likes, iPhone everything |

| 2020s | AI, ethics, and “should Mark be allowed to do that?” |

“Silicon Valley has always been a team sport: government money + academic talent + private capital. Not lone-wolf disruptors.”

— Margaret O’Mara, Author of “The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America”.

The Garage Myth

The legend will have us believe that Steve Jobs invented the future next to a lawnmower and storage boxes. Though he did do this on occasion, this is not how ecosystems are created.

The Valley’s growth came from:

- Military spending

- Immigration (the ultimate innovation engine)

- University-owned IP

- Venture capital ready to invest lucrative amounts of funds

“Silicon Valley succeeded because it had powerful friends in Washington and bold talent from everywhere else.”

— Margaret O’Mara, Author of “The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America”.

Basically: garage optional, great network required.

Dot-Com Era and After

The late 1990s dot-com boom turned Silicon Valley into the global face of tech ambition. Mass IPOs, massive valuations, and a bursting bubble in 2000–2001. Margaret O’Mara highlights that the burst forced the Valley to re-examine its business models and also reaffirm its resilience by pivoting toward Web 2.0 and the software-as-service age.

These decades shifted the Valley’s culture to “move fast, break things”. An ethos that became more visible globally. The idea that failure is part of growth, gained cultural weight. As companies such as Google, Amazon, and Apple rose from the collapse.

By the 2010s, Silicon Valley companies weren’t just building gadgets; they were designing digital life itself.

Facebook: How we remember birthdays

Google: How we remember anything

Uber: How we avoid parking

Apple: How we spend money (we don’t have)

They architected the attention economy with notifications.

Next: A Smart, Sustainable, and Inclusive Ecosystem

Silicon Valley is far more than a collection of startups, it’s an experiment. An experiment in innovation, in disruption, in the idea that the world can be remade. But experiments need ethics, too. If the early era taught us how to build wildly, the present demands we build wisely. Because the next big thing is not necessarily another unicorn, but a better ecosystem.

“Silicon Valley’s next chapter will hinge on whether it remembers that people — not products — are the true innovation engine.”

— Leslie Berlin, Stanford Historian and author of “Troublemakers: Silicon Valley’s Coming of Age”.

So if the Valley wants to remain the world’s innovation epicenter, it might need to act a little less like a disruptor and more like a good civilian. After all, the world doesn’t need more apps that deliver snacks. It needs a system that feeds everyone.

***

If you are fascinated by what is next for Silicon Valley, like the rest of us at the Design Matters Team. Then join our 3-day field trip to San Francisco on Jan 27-29, 2026. Sign-up is now open here.

Research Sources:

- Adam Fisher — Valley of Genius: The Uncensored History of Silicon Valley

- Leslie Berlin — Troublemakers: Silicon Valley’s Coming of Age

- Margaret O’Mara — The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America

- John McLaughlin — Santa Clara Valley Historical Association Archives