James Miller stood at a crossroads. His family’s bookstore, where three generations of East Londoners had discovered their favorite stories, was struggling. He had watched another local bookshop close its doors just last month, making it three this year. He had tried hosting community events and book clubs. He had cut costs everywhere he could without compromising service. But above all, he had watched helplessly as longtime customers, people whose reading tastes he knew by heart, drifted toward the convenience of online shopping.

James thought of his mother often these days. Her way with customers had been almost magical to watch. She had spent hours with them, not just recommending books but sharing in their lives. She had remembered which customer’s daughter was struggling with reading, which grandparent was recovering from an illness, and which teenager was looking for direction. She had known that helping someone find the right book wasn’t about algorithms or bestseller lists; it was about understanding their story. Could technology ever replicate that level of human connection, that ability to read between the lines and understand what a person truly needed?

Those are the opening words of “The AI Revolution,” a book that reached #1 on Amazon’s AI and business charts across multiple countries in July 2025. They were written by me – someone who had never written anything remotely resembling a book before.

In the months since, I’ve published insights on navigating AI that have reached hundreds of thousands of business and industry leaders. I’ve advised global organisations on AI implementation strategies that balance technological possibility with human reality. I’ve spoken at conferences from Cannes to New York City about the intersection of design, technology, and business transformation.

But a decade ago, I was a product designer at a creative agency, building startups and wrestling with the eternal challenge of making complex technology feel intuitive.

How did I get here? And more importantly, why are designers uniquely positioned to thrive in our AI-everywhere future?

Accidental Foundations

I never planned on becoming a designer. At 14, I was the kid spending weekends reverse-engineering websites and logos I admired, trying to recreate them pixel by pixel. I was fascinated by how visual choices could make complex information feel approachable and engaging.

By 15, this fascination had quietly become a business. Local companies started asking me to create their websites and visual identities. I had no formal training, no understanding of design theory, no business strategy – just an intuitive sense of what felt right and the persistence to iterate until it worked.

What I was really learning, though I wouldn’t understand this for years, was how to bridge the gap between complex systems and human understanding. Every project was essentially a translation challenge: how do you take what this business actually does and make it clear, compelling, and accessible to the people who might benefit from it?

This skill – translation between complexity and clarity – would become the foundation of everything that followed.

The Technical Detour

University brought a different path: computer science. Programming, algorithms, data structures – the fundamental building blocks of how machines think and process information. But the most formative part for me was a module on human-computer interaction that opened my eyes to how people actually engage with technology.

I learned that the most elegant algorithm means nothing if people can’t understand its output. The most sophisticated system fails if it doesn’t fit into human workflows. The most powerful technology becomes irrelevant if it doesn’t solve real human problems.

This technical foundation gave me a deep understanding of what’s genuinely possible and what’s not. I could engage with engineers as equals, understand their constraints, and push for solutions that were both human-centred and technically realistic.

But more importantly, it reinforced a core insight: technology becomes irrelevant if it doesn’t solve real human problems in ways people can actually use.

Finding My Voice in the Unknown

The next few years were spent at startups, agencies, and creative studios on zero-to-one projects – the kind of work where there’s no playbook, no established best practices, just a problem that needs solving and the creative challenge of inventing something new.

This was where I learned that design isn’t really about making things look beautiful – though that matters. It’s about making sense of complexity, finding patterns in chaos, and creating clarity where none existed before. It’s about translating between different languages: technical possibility and human need, business constraint and user desire.

Then came McKinsey – the world’s largest management consulting firm and a completely different scale of complexity.

Suddenly, I was working alongside deep technical experts and business leaders on extensive transformations at global scale. My role evolved from creating individual experiences to helping entire organisations navigate technological change. The scale had shifted, but the fundamental approach remained unchanged: start with empathy, iterate through uncertainty, find elegant solutions within constraints.

Then, in 2018, I found myself part of a diverse team – data scientists, engineers, designers – working on a machine learning model that would predict customer behaviour across retail touchpoints – AI implementations that would affect millions of users across global markets.

The scale was intoxicating, but it also revealed that the methodologies I’d developed for navigating uncertainty at startup scale became even more valuable when applied to enterprise complexity. The bigger the organisation, the messier the human and technical realities, the more essential it became to have someone who could bridge technical possibility with human adoption.

I discovered that my most valuable contribution was translation. Helping executives understand complex technical trade-offs while ensuring implementers stayed connected to business goals. Helping technical teams see how their sophisticated algorithms would actually be experienced by real users. Bridging the gap between what AI could do and what organisations should actually do about it.

The Leadership Translation

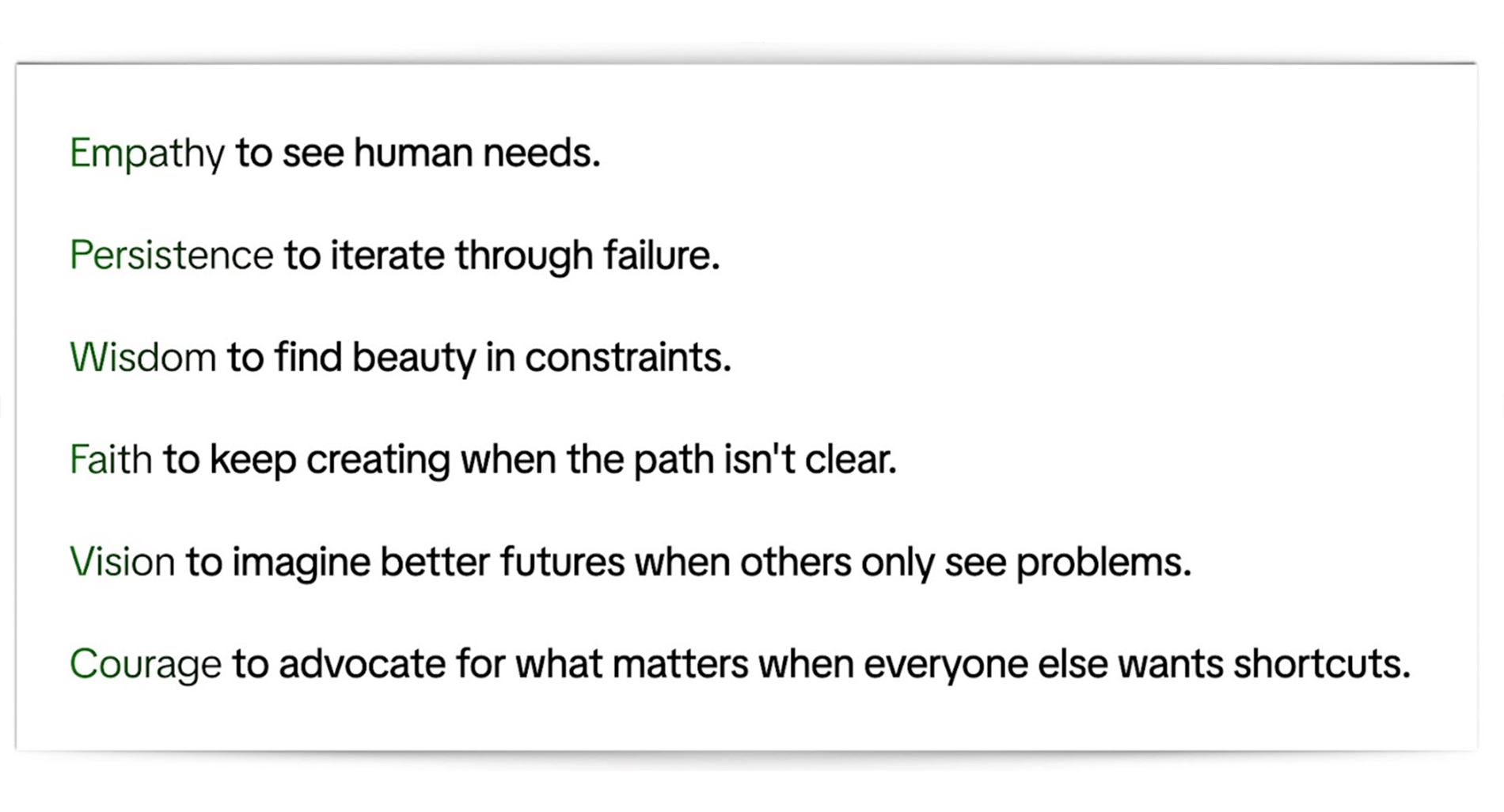

The real opportunity for designers in our AI-driven future is as strategists, translators, definers. We’re positioned to become the translators, the bridge-builders, the voices that ensure technological transformation serves human flourishing.

Every organisation needs people who can navigate the space between technological possibility and human reality, between innovation and adoption, between what AI can do and what it should do.

This requires more than interface design skills. It requires understanding organisational cultures, market dynamics, and stakeholder concerns that will determine whether AI implementations succeed or fail. It requires seeing AI tools as components in complex human and technological ecosystems that require thoughtful integration. It requires grappling with questions about algorithmic bias, human agency, job displacement, and privacy that technical teams often treat as secondary concerns.

And critically, it requires helping technical teams understand business realities, helping business leaders understand technical constraints. Understanding how people and organisations actually adapt to new technologies versus how we imagine they do.

These aren’t traditional design skills, but they build directly on design foundations. They represent the evolution from creating individual products to shaping technological transformation.

The Practical Opportunity

If you’re a designer wondering how to engage with AI conversations at your organisation, start with what you do best: reframing problems.

Your design background gives you unique credibility to raise these questions:

Your experience with user research translates to understanding how people will actually adopt AI systems versus how we imagine they will.

Your comfort with iteration translates to piloting AI implementations, learning from real usage, and refining approaches based on evidence rather than assumptions.

Your systems thinking translates to considering AI not as isolated tools but as components in complex organisational and cultural ecosystems.

Your advocacy skills translate to ensuring AI implementations serve genuine human needs rather than just technical possibilities.

The AI transformation is happening whether designers engage with it or not. But the quality of that transformation – whether it enhances human capabilities or diminishes them, whether it creates trust or resistance, whether it serves human flourishing or just business metrics – depends on voices like yours being heard in strategic conversations.

The Chapter Continues

The current AI implementation landscape reminds me of the early web – lots of technical possibility, but little consideration for human experience. We’re repeating familiar mistakes: building for technical perfection rather than human adoption, optimising for metrics rather than meaningful outcomes, treating people as users of systems rather than partners in solutions. The window for getting this right is narrowing. AI systems deployed without human-centred design don’t just fail – they create resistance, reduce trust, and make future implementations harder.

What James Miller, the bookstore owner from our opening, needed wasn’t more sophisticated algorithms – it was technology designed with human wisdom embedded from the start. His mother’s magic wasn’t mysterious; it was methodical empathy applied at scale. She understood that every customer interaction was a translation challenge: how do you take what you know about books, reading, and human nature, and apply it to this specific person’s unspoken needs?

This is exactly what designers do, and exactly what the AI world needs more of.

***

Want to follow Tey Bannerman’s journey? Then check out his platforms:

Website: http://teybannerman.com

LinkedIn: http://linkedin.com/in/teybannerman

*All images are provided and created by the Author of this article, Tey Bannerman.